Impressions from ARDD2024

In recent years The Aging Research and Drug Discovery Meeting has ascended as one of the most important aging conferences.

All your ERK are belong to us

This ARDD, Linda Partridge presented her work on the combination of trametinib and rapamycin. Trametinib is a MEK inhibitor that leads to reduced MAPK/ERK signalling and synergistic lifespan extension with rapamycin under some circumstances — even in F1 mice that pass the 900-day rule.

Hopefully they will pursue phase I studies soon, because I know for certain that we and others are interested in proper microdosing of trametinib. At the same time the ITP updated their webpage and announces that trametinib is in the ITP (which we knew through the grapevine). Interestingly, even Widaja et al. 2024 showed that pERK phosphorylation is up with aging and that this can be reduced by an anti IL-11 antibody, although I do not fully trust that data because I have rarely seen such strong anabolic upregulation with aging before. Be that as it may, an MAPK/ERK inhibitor is clearly an excellent choice to inhibit ERK!

It is amazing that MAPK/ERK emerges as the pathway that connects two of the most important mouse lifespan papers of 2024.

Continued rigorous study of reprogramming

I saw a poster from an NIH group (Luka Culig) who are working with an updated partial reprogramming regime. It’s almost a perfect update to last year’s ARDD poster by Alejandro Ocampo group showing that extensive reprogramming leads to lethality through effects on the liver and intestine. Luka is now running a lifespan study with thorough healthspan phenotyping using standard dox inducible reprogramming. The innovation is Cre-Lox mediated excision in liver and intestine. We will see if this can further improve safety and lifespan benefits.

The GLP1a nontroversy (I feel very strongly about the politics of this)

Not sure how much controversy there is hence the bad pun. Certainly, some people call it the end of obesity, others believe the GLP1 agonists to be longevity drugs. While this is exaggeration we do have a consensus that these are among the most promising gero-adjacent drugs that ever came to the market. Now where lies the disagreement?

Pharma, so far, refuses to run primary prevention trials with these drugs and many researchers nevertheless hail them as longevity drugs before the evidence exists, further reducing the pressure to perform good, rigorous validation. What we need is a large primary prevention trial. Period. Period. Someone needs to be brave enough to become a trillionaire, so please just do it.

No, seriously. This is something that has confused me for a while. Pharma is neither risk averse nor unable to perform large primary prevention trials. These explanations are often advanced for the lack of gero trials even though they fall short. We have seen pharma burn billions of dollars in the amyloid (and HDL cholesterol) hypothesis pit, so it cannot be risk aversion per se. Often you get lucky after iterating with a dozen of compounds that fail in trials. Most early amyloid antibodies failed and now we are getting some successes. Most CETP drugs failed and now we are also seeing the light at the end of the tunnel (obicetrapib). Thus burning money on initial high risk trials is not such a bad strategy…

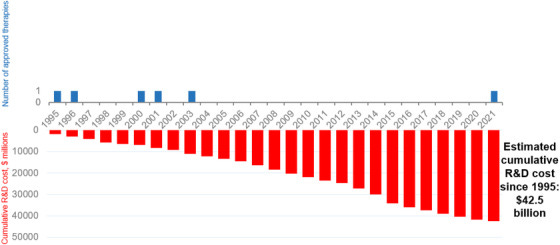

Costs of developing treatments for Alzheimer's disease

Didn’t you get the news? Pharma is too risk averse to fund gero trials.

Source: Cummings et al. 2022

Secondly, the NIH has performed at least a dozen gero trials, albeit using bad candidates, before we even started the TAME trial. They may not use multi-morbidity but they use even better outcomes: cancer, CVD and all-cause mortality. Trials with 10s of thousands of participants like VITAL, COSMOS or SELECT. Pharma clearly also has the money to run such trials occasionally. Taking these two facts together, the lack of risk aversion in pharma and their ability to run primary prevention trials, it is really astounding that they do not.

Some people believe these decisions are rational, or at least understandable, others strongly disagree. I would call these decisions highly irrational siding with the latter. My current theory is that they are driven by inertia and lack of biomarkers, because biomarkers — even if they are bad ones — do provide some level of (false) confidence in early trial stop-go decisions.

The food - who stole all my fruits?

Tomas joked that I will complain about the food and right he was. The situation is much improved compared to the last few years but leaves room for further improvement. I do realize the bar is important, but conferences really do need to step up the healthy food game. For example, the breakfast. It’s good. The yogurt is absolutely amazing and not too sweet. Unfortunately the healthy choices for vegans approach zero. Bread rolls with cheese, yogurt and some pastries. Please, at least serve fruits at every break if you cannot serve the hummus at every break (which would be desirable IMHO).

We should lead by example. Lots of us are trying to improve the “reputation” of longevity research. Maybe we could start by being healthy ourselves instead of banning the use of the word “longevity”? (see below, and I am looking at you Altos labs)

Screening predicted hits and non-hits?

Lots of amazing computational work was discussed in the Munk cellar.

It seems everyone and their grandmother is doing AI/ML now. Whether the bubble bursts or not is irrelevant; AI/ML models certainly have a role to play and are here to stay. Plenty of groups also do “simpler” predictive work based on graphs and/or omics, e.g. linking CMAP with omics of different model species. My main worry is that we are not rigorous enough about the testing of our candidates. We should pick neutral candidates, as well as negative and positive controls so that we can have a statistical, or at least intuitive, comparison between these groups. If you predict 3 compounds from set X and one of them works to extend lifespan does this mean you predicted well or maybe you have a lucky set of X, or just luck in your experiments? How much better are you than chance? Can your model predict compounds that accelerate aging too?

Plenty of other people have (annoyingly) written about the methodical shortcomings and controversial issues in longevity research that I do not always agree with e.g. Dan Ehninger, Charles Brenner @CharlesMBrenner or Jamie Timmons @metapredict. And I do think there are a lot of issues worth pointing out, ways in which we should do more rigorous science, issues we should be honest about.

Terminology and neurobiology — do we even have a reputation problem to begin with?

Some minor comments that came to my mind during the neurobiology sessions. One of the speakers was talking about the prevalence of brain volume and blood flow reductions, as well as microbleeds with aging. While another speaker, Saul Villeda, was talking about the neurologic and health benefits of exerkines like CXCL4 (PF4) and Gpld1 (isn’t this the one also identified by Rich Miller?). However, this is not what I want to highlight here.

What I noticed is that there is a proliferation of problematic terminology: healthspan, health, healthy aging, normal (“aging is normal”) etc. These words are often used in an attempt to improve the “reputation” of geroscience. This strategy is ill-conceived if you ask me.

Please don’t use the word health in an exclusive context, as in: “What does your company or lab do?” “We work to improve age-related health”. Come on, literally every company works to improve health and the majority of them is working to improve age-related health! What makes you special? What makes our science special? If your claim is that biogerontology is just a run off the mill field and we do not deserve increased funding then fine, go ahead and use this word. Otherwise I highly recommend to use the terminology set out in e.g. the Longevity Dividend or the definitions underlying the Geroscience hypothesis. Basically, we aim to slow aging because it is order of magnitude more efficient than trying to (merely) improve health. Is this sentence not good enough for an interview or talk?

Please don’t use the word healthspan in an exclusive context no matter how attractive it might seem to you. Apart from some definitional issues (see Rich Miller on the VitaDAO podcast), the main problem is two-fold. We did a survey in Singapore and half of the people have no idea what the word even means whereas everyone understands the meaning of longevity. The second problem is the same as for health, the term by itself weakens our science instead of strengthening it. Bad advertising. Hence I prefer the terms “healthy longevity” or “lifespan and health(span)”.

I am also weakly opposed to the usage of normal in the context of aging for the following reasons. Normal has two meanings, one is “common” and another one is “acceptable”.

A: I am worried about this weird shadow on my MRI.

B: Don’t worry, that is normal.

A: My girlfriend just broke up with me, I feel like shit.

B: That’s normal!

The implication of the word is usually: okay this happens, don’t worry, deal with it. But if we want to improve the funding situation for longevity research, if we want to help billions of people, we cannot just accept aging as normal. We need to fight aging without disrespecting older people. I do not think using the word normal is necessary to show respect. For some odd reason we talk about normal aging and normal decline a lot. No one would use this terminology for cancer, don’t worry it’s normal to get cancer, oh it’s normal. Nothing is normal here. Minor cognitive decline during aging, moderate cognitive decline during aging (loss of fluid intelligence) and cancer are all age-related conditions and none of them are normal. They might be part of normative aging sensu strictu but we have to be careful not to be too euphemistic about the reality. It is hard to put this into words, but these words matter, especially to politicians, policy makers and laypeople.

Healthspanners in the streets, lifespanners in the sheets, as the joke goes. We will support your coming out when you are ready, do not worry.

I take whatever works in mice

The record stack I heard someone at ARDD is taking consists of 60 supplements. They reasoned that any drug which works in mice must have a good risk/benefit ratio in humans. While I may not agree to that extent, I do believe that supplement combinations are safer than expected. My own approach would be to combine rigorous mouse data with human safety and efficacy data on intermediate outcomes. This is one of the uses of the 900-day rule we recently published. If you want to rely on mouse studies, at least rely on strong mouse studies.

Pabis, Kamil Konrad, et al. "The impact of short-lived controls on the interpretation of lifespan experiments and progress in geroscience." bioRxiv (2023): 2023-10.

Widjaja, Anissa A., et al. "Inhibition of IL-11 signalling extends mammalian healthspan and lifespan." Nature (2024): 1-9.

Gkioni, Lisonia, et al. "A combination of the geroprotectors trametinib and rapamycin is more effective than either drug alone." bioRxiv (2024): 2024-07.